The Scientist In Science

What—and who—is involved in science?

I would like to make a straightforward point in this essay. This is: What we call objective science always involves a subject.

On the one hand, this seems obvious. Where else does science come from, if not from scientists? At the same time, scientists are often regarded as standing outside of their experiments. Science is increasingly understood as objective. But this framing unfortunately neglects the subjects who conduct it. The astronomer today sees Jupiter with beautiful clarity, but he does not see himself seeing the gas giant! The cosmos he observes more and more of increasingly is one which he finds himself in less and less. But is this the right way of viewing things? Must more objective science necessarily lead to greater displacement for subjects? Or is there another way of viewing science?

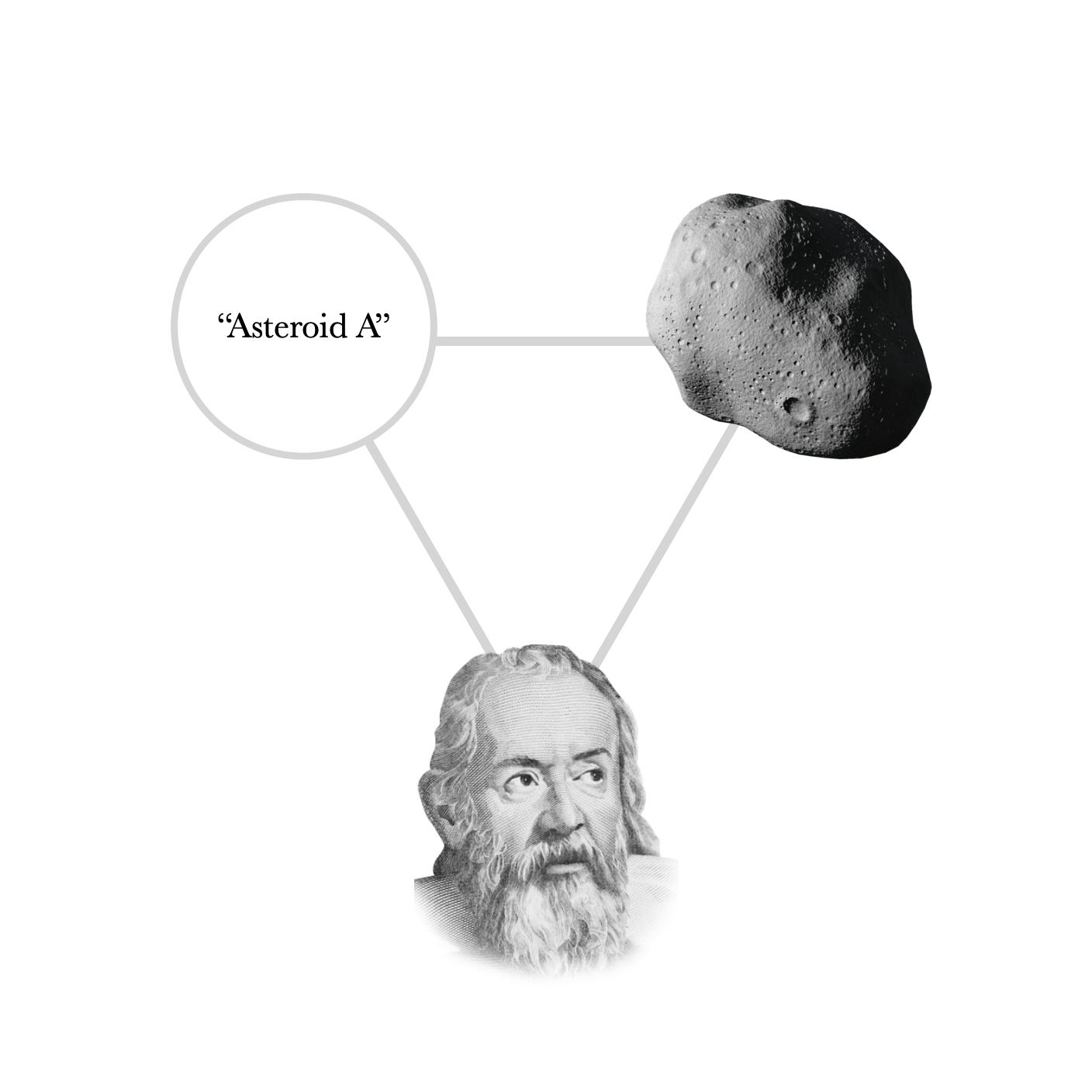

Let us consider a simple statement: This is Asteroid A.

Simple indeed! This basic classification appears to have only one entity in it, the asteroid. How much more refined can something get?

But, it turns out, there are not one but three entities involved in this statement!

The name Asteroid A

The rock in space to which the name refers

The scientist who names this rock Asteroid A

Science is always and irreducibly composed of a described, a description—and a describer. A thing, such as a rock in space, in-and-of-itself is not science. A description, such as the name Asteroid A, is also not in-itself science. A scientist, too, does not alone make up science. Rather, science results from the relation between the observed, the observation, and the observer. The measured, the measurement, and the measurer. The named, the name, and the namer. This triadic relationship is involved in every step of the scientific method. Remove any one or two of these components and science no longer remains.

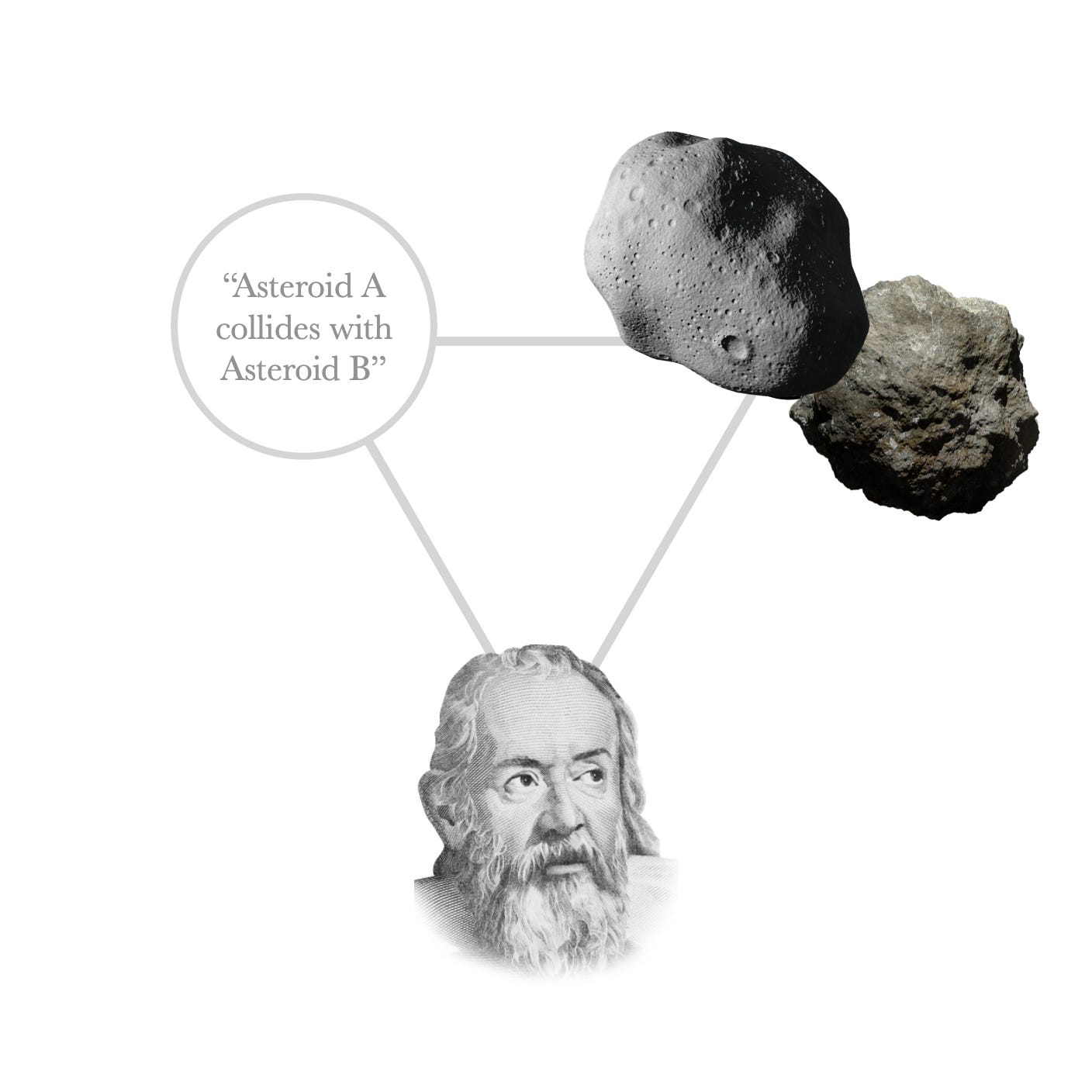

American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce, in the 1800s and 1900s, resolved this blindspot in our worldview—though admittedly his insights have not yet caught on. Peirce realized that there are three modes of being, which he termed firstness, secondness, and thirdness. Firstness is a thing-in-itself independent of everything else. Secondness is two entities in reaction to each other. Thirdness is when a third entity mediates between two others—and this is the mode of being modern science does not take into account.1 When Scientist D makes Statement S describing Collision C, this cannot be described as D causes S which causes C (D—>S—>C). Rather, Scientist D mediates between Statement S and Collision C in what may be irreducibly described as Statement △SCD!

Scientist D—let us call him Jim—who is currently glancing at his watch to see if he will make it home in time for dinner with his wife and kids, is irreducibly part of the scientific process! Jim, looking out from his eyeballs over his partially blurred nose to see sunlit rocks crash into each other, is himself related to the collision. Jim is real. The asteroids are real. Their collision is real. The statement is real. The relation between the collision, the statement, and Jim is real. And this relation between the collision, the statement, and Jim is what makes science, science.

We have come to think of science as only what is observed—but this crucially leaves out the observer. A full account of science, however, should always include the observed, the observation, and the observer. When the good folks of LIGO in Louisiana detect gravitational waves from black holes billions of miles away, we should celebrate this but remember that neither the collision of black holes nor just their measurement is science. Rather, science is the relation between the collision, the measurement, and the scientists themselves. Science is always triadic—it always partakes in thirdness—and the scientist is always a part of this relation.2 Rather than being a transcendent observer hovering outside of the cosmos looking in, the scientist is always in and in-relation-with the cosmos he or she observes.

Peirce showed in his writings than anything above three entities engaging with each other can be reduced to one of these categories, while the categories of firstness, secondness, and thirdness are irreducible to each other. For instance, a pot of boiling water involves countless water molecules bumping into each other; but in principle this can be described as a chain of Secondness: Molecule A bumps into Molecule B, B—>C, C—>D, and so forth.

To be technically precise, Peirce’s thirdness is constituted by signs which he defines as the irreducibly triadic relation between a representamen, object, and interpretant. This last component is not the same thing as an interpreter, i.e. a person, or in our specific case, a scientist. The interpretant is the active mediator between the representamen and object as well as the meaning itself or effect of the meaning resulting from the representamen and object being linked. In the case of science, however, the interpretant—which may be thought of as the active understanding of one thing (the representamen, the observation, the measurement) meaning another (the object, the observed, the measured)—always takes place within the scientist. The scientist is always involved in science, in the triadic relationship, though the scientist is perhaps better thought of as the necessary entity in which the interpretant (the meaning, the understanding) exists rather than the interpretant itself.