Mimesis As Semiosis

What most distinguishes humans from other animals? Imitation? Or symbols? Both?

Note to the Reader: Hello dear Reader! Thank you for checking out this article. This week’s essay is a bit longer and denser than usual, as it is my initial draft of an essay I am hoping to have published in a philosophy journal soon! I am planning on getting back to shorter and much more accessible essays next week, though it seems like it could be fun to sprinkle in a more advanced paper every now and then. Would love to hear your feedback on if you’d prefer to solely read short or long essays or a mix of both.

Again, many thanks for reading! —Caleb

“Man differs from other beasts in his capacity for imitation”—Aristotle

“What distinguishes the human being from the other animals is that only human animals come to know that there are signs”—John Deely

Part I: Intro

The primary goal of this paper is to help reconcile the theory of mimesis and mimetic desire put forth by René Girard with the theory of semiotics—the study of signs, symbols, language, and meaning—most thoroughly developed by the American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce. I would like to propose in this paper that we engage in mimesis because we engage in semiosis; in other words, we are capable of imitation because we are symbol users. Further, I propose that mimetic desire is one particular instance, or subset, of semiosis.

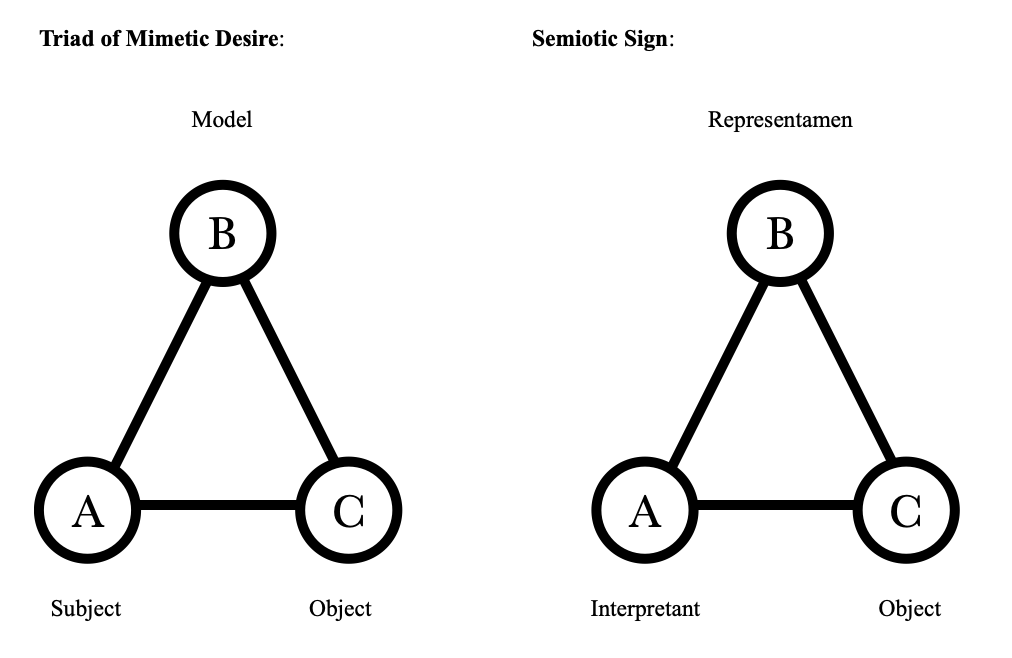

Let us briefly define terms here. By mimesis, I mean imitation. By mimetic desire, I refer to the concept proposed by Girard that we tend to desire things not because the object in-and-of-itself is desirable but because we observe someone else desiring it. Mimetic desire is therefore composed of three elements: an Object, a Model, and a Subject. The Object is a thing-in-itself. The Subject is a person. The Model is a person that the Subject observes wanting the Object. By semiosis, I mean the action of Signs. By a Sign, I refer to the concept most clearly defined by Charles Peirce as the irreducibly triadic relation between an Object, a Representamen, and an Interpretant. By an Object, I mean a thing-in-itself, whether ens rationis or ens reale—a mind-dependent or mind-independent thing. By Representamen, I mean the thing that stands in for or represents the Object, as a word, image, or sound, etc. Finally, by Interpretant, I mean the entity that couples the Representamen to the Object, which in human semiosis typically refers to one’s Self.

I hope by the end of this paper to show that the triad of mimetic desire involving the Object, Model, and Subject is the same triad as the semiotic Sign which consists of an Object, Representamen, and Interpretant respectively. They are the same process, in other words, with the former being one instance of the latter.

Why seek to reconcile mimetic theory and semiotic theory at all? I believe this is a worthy endeavor for a few reasons. The first is simply that I believe it to be true that mimesis and mimetic desire derive from our semiosis, and it therefore seems reasonable for me to say so. Further, as Girard says, “No question today has more of a future than that of Man”. The modern anthropology of Man as fundamentally and essentially an isolated and independent individual has become not only stale but even a deadly falsehood in our modern world. In an effort to update our anthropology, it seems reasonable to look to perhaps the most prominent development in anthropology in recent decades as a starting place, and that is Girard’s idea that we are inherently mimetic creatures and that even our desires tend to be imitated. This concept of man as an imitator in-and-of-itself suggests that our very essence might have some element of relation to it. That said, there is sometimes a tendency amongst Girard scholars and followers to in a sense be “mimetic reductionists”, reducing the human person to simply an imitator. Girard himself remarks that “Neurologists remind us frequently that the human brain is an enormous imitating machine”. In a way, this tradition goes back even to Aristotle who claims that “Man differs from other beasts in his capacity for imitation”.

We of course do differ in our capacity for imitation, but is that the cardinal difference between us and other species? Why do we imitate in the first place? What gives rise to imitation? What is really occurring when a Subject desires something because a Model is desiring something? Peter Thiel, a student of Girard and himself a philosopher-king of Silicon Valley, remarks that “the new science of humanity must drive the idea of imitation, mimesis, much further than it has in the past”. I believe the best way of doing this is actually by transcending mimesis in a way, situating mimesis within the broader framework of human semiosis. By showing how mimesis arises from semiosis and how mimetic desire is a subset of semiosis, one can fully recover and embrace Girard’s ideas of imitation while providing an even more encompassing definition of what it means to be human.

Part II: The Semiotic Self & Mimesis

I hope here to first explore how us being semiotic creatures gives rise to mimesis and mimetic desire. I will attempt this by using insights from the book Lost in the Cosmos by novelist and lay semiotician Walker Percy.

According to Percy, once a creature crosses the threshold into semiosis, they no longer exist solely in a mind-independent environment, but also in a mind-dependent world. This is a world of signs. There is considerable overlap between the environment and a person’s symbolic world, but they are not the same. There can be things in the environment which may not be in a person’s world—such as a planet they have never heard of and therefore do not have a Sign for. And there may be things in a person’s world which may not be in the environment, such as unicorns. Every Object in their world gets assigned a label (i.e. Representamen), and as for the gaps in their world, these come to be labeled as gaps. The semiotic creature’s world therefore is a complete world and is entirely filled with Signs.

Semioticians thus far have given great focus to studying Signs in the “outer world”—which we may define as the world outside of one’s Self—whether they be various types of ens rationis or ens reale Objects. As Percy points out, however, little has been done by way of determining what happens when the semiotic Self turns inward to focus on itself. He declares that while Signs can help us understand everything in our Outer World, our knowledge through Signs breaks down and “sparks begin to fly” when the semiotic Self seeks to know itself. The hypothesis he proposes for why this happens is that the Representamen of one’s Self is much “looser” than it would be for any Object other than one’s Self, and that all Representamens could apply equally to describe one’s Self.

Percy has indeed hit upon something incredibly profound in observing that the semiosis which helps us know about everything in our Outer World breaks down when one seeks to “know thyself”. This is indeed very true. That said, while all Representamens may equally apply to one’s own Self, this seems to be a byproduct rather than the fundamental problem that causes the semiosis of one’s Self—which we may term Self-Semiosis—to break down. Instead, I believe the fundamental reason why Self-Semiosis is inherently impossible is because in the semiotic Sign of one’s Self, the Self is both the Interpretant and the Object. A Sign requires three distinct entities to be a Sign, but in Self-Semiosis there are only two distinct entities, namely a Self and a Representamen. This is why you can know other people and things much better than you can know your own Self, even though you have been with your Self for your whole life. You can know things about yourself just fine, but when it comes to knowing your Self as Self, you have reached a limit of semiosis. This is similar to how modern physics works well until you get to a singularity at the center of a black hole or at the beginning of time. At these points, the otherwise functioning physics generates an “Error”. Similarly, we may describe a Semiotic Singularity as an instance in which semiosis breaks down due to circumstances which cause the collapse of the Sign. Self-Semiosis is inherently impossible because of the Semiotic Singularity produced by the Interpretant and the Object of the Sign being identical. We are simply too close to ourselves (in fact, identical with ourselves) to know ourselves, at least through semiosis. Percy rightly concludes, “The self has no sign of itself”.

Just because Self-Semiosis doesn’t work, this does not stop our Self from trying to place itself in its Sign-filled World. How then do we go about trying to assign a Sign to our Self? As Percy declares, our Self does this “often by identifying itself with other creatures in its world. Among Alaskan Indians, this practice is called totemism. In the Western world, it is called role-modeling.” Here we finally begin to see how the semiosis that helps us understand the cosmos can give rise to imitation. Percy gives the example in his book of practitioners of Totemism who identify their Self with something in their Environment, such as a parakeet. This leads the person to mimic the parakeet. In the case of role-modeling in the Western world, one may choose to imitate one’s parent or a celebrity or a saint—any person in one’s Outer World—for instance, in an attempt to provide an identity for one’s Self.

One can also imitate in order to better understand one’s Outer World. When a baby sees an Object which she’s never come across before, and you say the word ball, the baby might repeat the sound ball, thus assigning a Representamen to that Object in her Environment.

Semiosis can therefore give rise to imitation in order that we may better understand both parts of our World—our Outer World as well as our Self in that World. As Girard concludes, “all learning is based on imitation”.

Part III: Mimetic Desire as Semiosis

Now that we have seen how semiosis can lead to mimesis in general, I would like here to show that the triad of mimetic desire (composed of the Subject, Model, Object) and the triad of semiosis (Interpretant, Representamen, Object) are the same triad. They are the same process. In mimetic desire, the Model becomes a Representamen (a symbol, to use the lay terminology) of the Object. The Model comes to represent the Object.

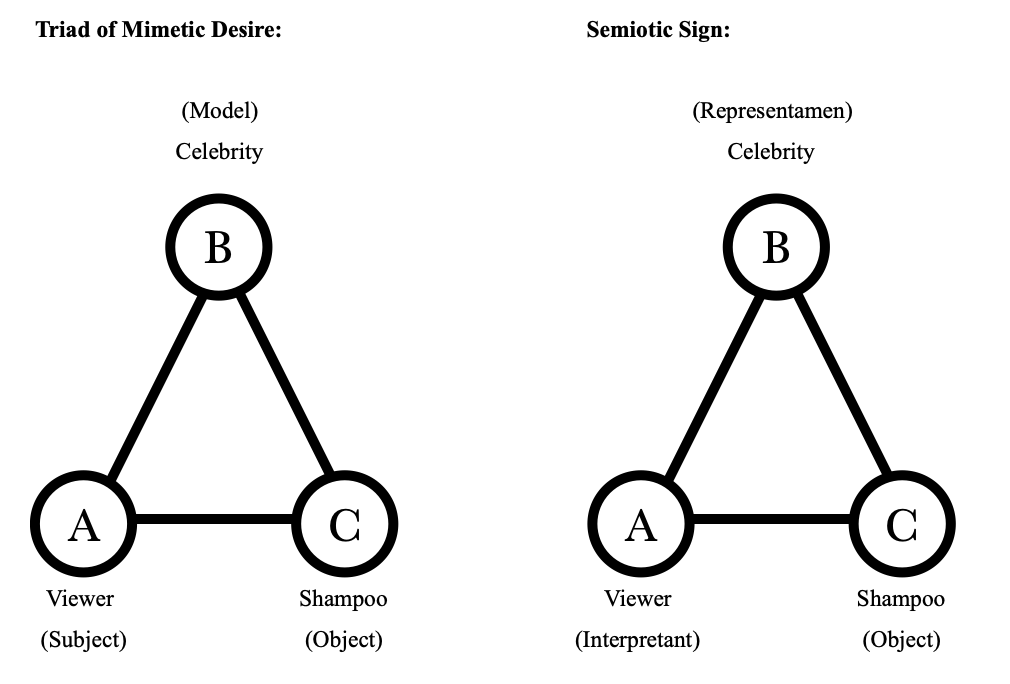

Let us offer an example to illustrate this point. Suppose a person views a television ad for shampoo that features a celebrity who is endorsing the product.

We can say that the Model from a mimetic desire triad is a particular type of Representamen, which we can label a Model Representamen. We can define a Model Representamen as a Representamen comprised of a human being who desires the Object of the Sign of which he or she is a part. Further, just as Charles Peirce identified multiple types of Signs, such as Icons and Indexes, we can propose here to add one more type of Sign that we may call a Mimetic Sign. We may define this as being composed of an Interpretant, an Object, and a Model Representamen. We can further suggest one additional term, namely Mimetic Semiosis, which we may define as the action of Mimetic Signs.

Mimetic desire is therefore a particular type of semiosis, and we are capable of mimesis because we are capable of semiosis. To the extent that one is semiosic, to that extent will one have the capacity or inclination for mimesis. This may be helpful to consider as we seek to update our philosophical anthropology for the coming era. As the premoderns held that man was a rational animal, and the moderns have embraced the res cogitans anthropology of Descartes, I believe that instead of replacing these with the imitating animal as our true essence, it may be better to embrace what philosopher John Deely and others refer to as the semiotic animal as the basis for our truly post-modern philosophical anthropology.

Something to consider!